The Danish island of Mön in the Baltic Sea is not only popular with summer vacationers and bathers, hobby geologists have long been drawn to Mön’s famous cliffs, because fossils with an age of up to 70 million years can be found in the scree at the foot of the chalk cliffs .

Originated in the Cretaceous Period

In the Upper Cretaceous Period, about 70 million years ago, there was a shallow sea area between what is now southern Sweden and the Harz Mountains, which offered optimal living conditions for a large number of marine creatures such as mussels, crustaceans and cephalopods. If such an animal died, it sank to the sea floor, where in most cases it was quickly decomposed by various microorganisms. However, if the carcass was covered by sediments, it could happen that the decomposition process was stopped due to a lack of oxygen. So the remains were preserved and over time mineral solutions could seep in there, which petrified the carcass of the animal in a process that took many millions of years and under the pressure of great depths.

The chalk cliffs of Möns Klint

With the end of the Cretaceous Period, there was a strong sea retreat and large parts of this shallow sea fell dry. In the last Ice Age, the chalk cliffs that form the Möns Klint cliff in the east of the island of Mön finally emerged. The light chalk, in which countless fossils are enclosed, was pressed up from deeper layers by the pressure of the ice sheet.

Today, fossil collectors like to visit Möns Klint because, unlike many other sites, all fossils collected here can be taken home with you.

The beach at the foot of the cliffs is easily accessible for tourists, albeit quite impassable, as it consists exclusively of flint rubble. Both the mostly fist-sized flint stones and chalk chunks can contain fossils and in the summer months you can only make really interesting discoveries with luck, as many tourists look for fossils on the beach of Möns Klint during this time. The chances are much better in autumn and winter, when the chalk cliffs are removed by rain, storm and frost and new fossils are exposed. During this time, however, the risk of landslides and falling rocks is particularly high and staying at the foot of the cliffs is not without danger.

Fascinating finds

However, many hobby geologists are happy to accept this risk, because Möns Klint offers the attentive fossil collector a multitude of interesting fossils from the Cretaceous period.

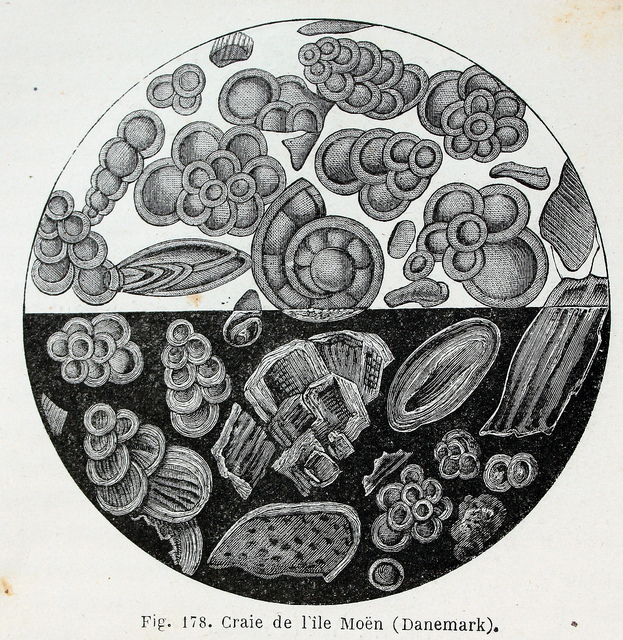

The so-called thunderbolts are among the most common finds. These finger-shaped fossils are parts of the inner skeleton of so-called belemnites, cephalopods that resemble our present-day squids. Petrified oysters and sea urchins are also not unusual finds here.

Fossil corals and the well-known ammonite shells, which resemble snail shells and were home to cephalopods, are rarer. The ammonites have long been extinct, but today’s animal species Nautilus is very closely related to them.

The so-called rattle stones are popular, albeit difficult to find. These are round flint stones, inside of which a loose fossil pebble sponge makes a rattling noise, as sea water could penetrate through a small hole and wash out the chalk that surrounded the fossil inside the flint stone.